This article was originally posted on EdSurge on October 10, 2012

What does the Maker movement have to offer education? One compelling idea is what some many consider to be an upside-down way to learn.

What does the Maker movement have to offer education? One compelling idea is what some many consider to be an upside-down way to learn.

Larry Rosenstock, founder of High Tech High, started me thinking about this idea in a conversation we had on project-based learning. He pointed out that most programs teach kids in advance the skills they will need to succeed at the project, but Larry believes that the students should learn the skills as part of the project – just at the moment they need them.

For example, if one were to teach skills in advance for, say, scientific data collection, a teacher might show students pictures of the equipment they will use, test them on their ability to describe the function, demonstrate how to organize their data and warn them to label their axes–a somewhat mind-numbing approach.

Consider instead the opposite approach–laying out the objective of the lesson, and then helping students discover what tools will help them reach their goal. Imagine, for instance, that a teacher organized the lesson around activities such as determining water quality, cataloguing wildlife, or building a nature trail in uneven terrain. Students will wind up becoming deeply engaged in both the task–and in how to accomplish it. They may at times get frustrated–but then the smallest hint will send them seeking (and finding!) knowledge, and specialized equipment and tools, all of which will be seen as treasured gifts. What a beautiful and counter-intuitive way to think about teaching and learning!

It’s the difference between passively accepting data and actively seeking knowledge–a difference that involves mindset, disposition, context, purpose, authenticity, and a pack of other finely nuanced technical terms.

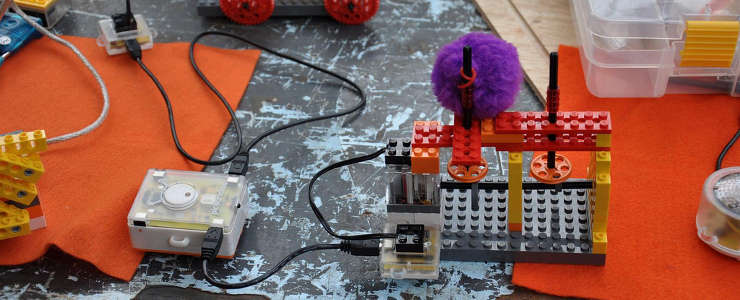

The Maker community takes an important step even beyond project-based learning in that the projects and goals themselves are chosen and initiated by the Makers involved. Makers choose to Make–whether they display the results in a booth at a Maker Faire, or have an ambitious project of their own that they want to bring into the world. The challenges they encounter are their own challenges and the learning happens on the way to creating something.

The Maker community provides an environment and context for learning to Makers of all ages. One of the salient characteristics of this community is the urge to share–projects, skills, materials, and resources are available to anyone who has the desire to learn. And the Maker Faire gatherings provide a wonderful opportunity to find experienced Makers who can point a novice in the right direction. Online resources abound and many cities now have Makerspaces where Makers have access to industrial equipment and fellow enthusiasts.

Novices learn through the guidance of more experienced Makers and over time become adept in finding and accessing the resources they need to accomplish truly amazing things. Not only do they acquire specific skills–building a circuit, programming an Arduino, or welding the joints of a robot, for example–but in doing so they learn how to learn. In short order, novice Makers become contributors–perfecting a new technique, combining materials in a new way, sharing their discoveries back with the community, and perhaps helping newcomers to find their way in turn.

Since Makers are focused on doing, rather than learning, the question “Why do I need to know this?” becomes irrelevant. As Makers participate in different physical and virtual communities, they learn both the “hard” skills needed to complete a successful project and the “soft” skills of collaboration and communication that we all use as productive citizens. Since every project is unique, Makers are often faced with fresh opportunities to find a new way to learn or a new source of information. What better example of an environment for learning could there be?